|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Retrogaming |

Mainframe Zork(This is a continuation of earlier articles about Zork I and Mini-Zork.) Contents

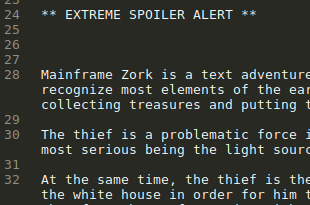

Brief background Brief backgroundCompared to Colossal Cave, Zork portrayed a slightly more coherent world (not being set in a natural cave but in the remnants of the Great Underground Empire) and had a more advanced parser, which is able to understand more than Cave's two-word verb-noun sentences. At some stage in its development Zork was renamed to Dungeon, then re-renamed Zork after a company called TSR claimed priority of the name Dungeon for one of their own games. Eventually Zork was ported to smaller computers, starting in 1980 with the PDP-11, the Tandy TRS-80, and the Apple II. As the memory sizes of these machine were relatively small, Zork was published in segments as seperate titles — Zorks I, II, and III — and became the first product of a newly founded company called Infocom. In the meantime, the original mainframe version of Zork had been distributed with its source code on ARPANET and could be played freely by the few who had access to a connected PDP-10 (to distinguish between the original Zork and the commercial Zorks, the former will be indicated as Zork/Dungeon or Mainframe Zork for the remainder of this overview). Bob Supnik, a DEC engineer, endeavored to port the game to the smaller and more common PDP-11 and from MDL to the FORTRAN programming language (the Colossal Cave adventure was also written in FORTRAN). This port was then distributed through the legendary Digital Equipment Computer Users' Society, or DECUS. Through the years, the open source Zork/Dungeon has continued to be maintained and to exist alongside the commercial Zork I, II, and III games, and has been ported to other platforms and programming languages. The history of Mainframe Zork has been described in detail by a number of people, amongst whom some had been directly involved in its development. For further reading, watching, and listening, try the following:

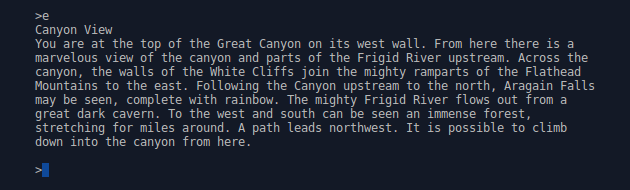

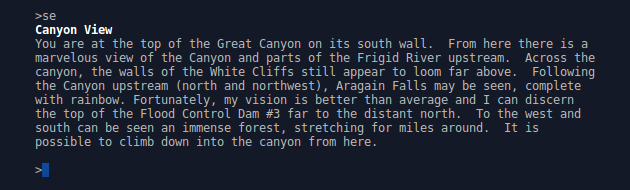

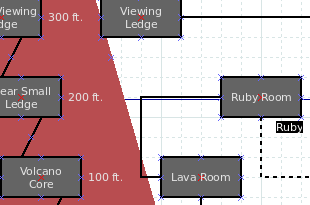

Playing Mainframe ZorkA veteran of Zork I who starts playing the latter's progenitor is likely to feel a mixture of familiarity and bewilderment. The surroundings of the White House are subtly but noticeably different; essentially the same, but navigationally not. The forest seems a bit more labyrinthine, but especially arriving at the Great Canyon will cause some brows to furrow on account of its orientation in the land. Specifically, the canyon and the Frigid River seem to be somewhat undefined with respect to the course of the river after the Aragain Falls.

Nevertheless, gaining entrance to the underground for the first time is done in exactly the same way. A delightful element specific to Mainframe Zork is the issue of US NEWS & DUNGEON REPORT that lies in the living room of the white house. This publication tells the player about the changes and improvements in the version that he is currently playing.

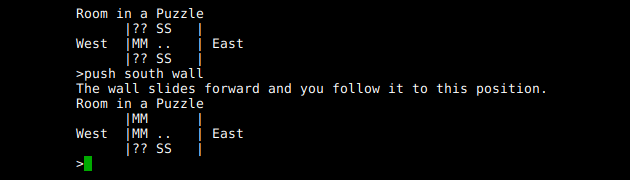

The passages in the underground world wind and turn more than those in the other versions of Zork. This means that a passage from one room to another room is not always reversable; i.e. moving east after first having moved west does not always bring you back to the first room (this phenomenon is more common in older text adventures than in newer). Even more disorienting is the Round Room, situated in roughly the same location as its namesake in Zork I but functioning like the Carousel Room in Zork II. This location has the effect of interfering with the player's intended exit direction and so breaks some of the clockwork predictability found in many text adventures. For these reasons, mapping the game is quite a chore but nevertheless quite useful, as the game is positively huge. Most item descriptions are somewhat shallower than those found in later works of interactive fiction; examination of many objects will result in a "I see nothing special about the ...". Also, in room desctiptions objects are sometimes described using more elaborate terminology than is recognized by the parser if the player wants to address that object. Some of the most infamous puzzles found in early Infocom games make their first appearance in this Zork, such as the one involving the Bank of Zork where the outcome of a translocation device in a certain location is determined by which room the player has arrived from. Another example is the Royal puzzle, which is an implementation in text of the Sokoban puzzle game. Perhaps these puzzles illustrate how the authors explored the possibilities of the fledgling interactive fiction medium

Mainframe Zork is distinctive in another way — it actually consists of two consecutive games. Once the player has amassed all treasures found in the initial game area, he is pronounced worthy of a further challenge and a break is made with the former. He is transported with only his lamp and his sword to a new dungeon, where a fresh score counter is started and where a new treasure (and job title) lie waiting at the end. Versions and portsFollowing the thread of versions of Zork/Dungeon is an interesting pastime in itself. Coverted from MDL to FORTRAN to C, the game is a remarkably long-lived phenomenon in the history of computer hardware and software development. Both its contents and the interaction with the player have remained unchanged after having been ported from the room-filling PDP-10 to smaller machines to multi-media capable consumer-level computers and eventually to smartphones; a journey similar to that of Zork/Dungeon's progenitor, the original Colossal Cave Adventure. Many versions can be found in various locations on the Internet, one of the most accessible being a port to the Inform language (itself a descendant of the development mechanism used at Infocom) which makes the game essentially platform independent. The table below contains some links to Zork/Dungeon for various computing environments (but many others exist). Yellow links indicate that the site from which a particular version was downloaded has disappeared, and that I keep a copy on my own site.

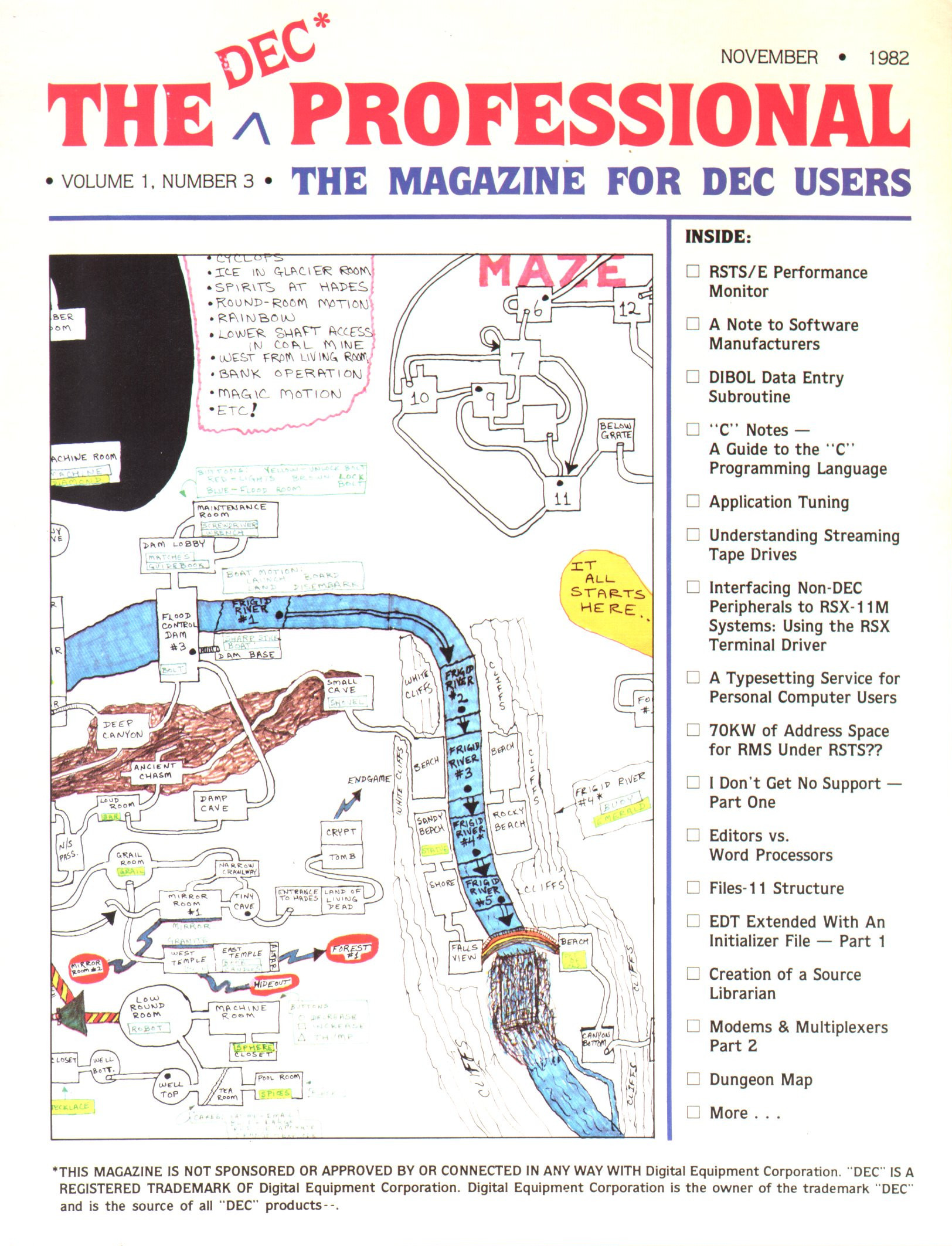

The FORTRAN and C versions are of course only playable after building an executable with an appropriate compiler. The most convenient way to play the game would be to get the Inform edition and play it with a modern interpreter; it features multiple saves and a status line that shows location, score, and number of turns. From a historical point of view it would be interesting to try the original in MDL; to run Zork/Dungeon on a modern machine (i.e. not a PDP-10) you need the Confusion MDL interpreter that can be found at the Interactive Fiction Archives. The last release of Mainframe Zork by Infocom occurred in July 1981. Zorks I, II, and III were published respectively in 1980, 1981, and 1982, according to the Infocom fact sheet. Solution and map (spoiler alert!)The November 1982 issue of DEC Professional journal features a famous hand-drawn map of this version of Zork by a certain Steven Roy. And recently, an older map by Dave Lebling, one of the game's authors, has surfaced on the Internet. It is interesting to compare the two, especially the differing location of the white house relative to the canyon and the Frigid River that flows through it.

(Even more) Links

(Originally published 2019/03/15)

|